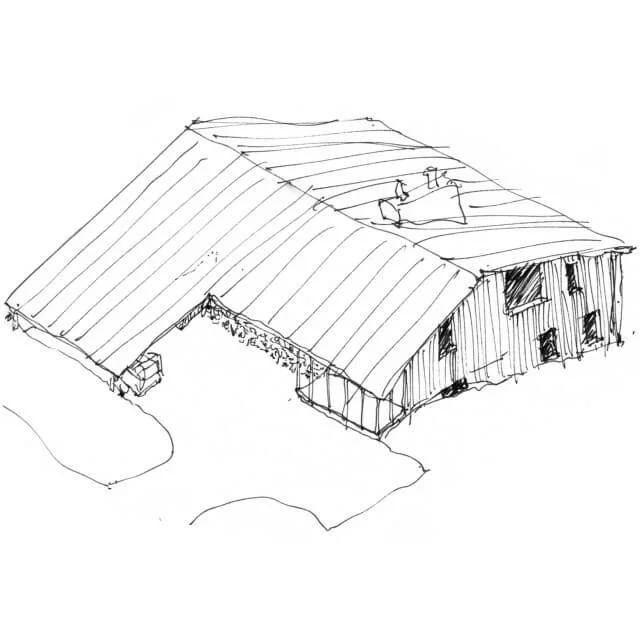

At the bottom of the field in front of my house is this shabby Dutch barn. Most people’s reaction is ‘I bet you wish that barn wasn’t there’, but I actually rather like it. It is prominent but doesn’t block the view. There aren’t many buildings I’d be happy to see there but this utilitarian shed represents something about why I moved to the country and how man and nature co-exist in the English landscape.

Its frame is made up of slender steel posts and rails that are just sufficient to do their job. There is no redundancy in the structure and each component is doing what it appears to be doing. The joints are simply bolted and the corrugated steel cladding sheets are screwed on so that individual pieces could be easily replaced if necessary or the whole thing taken down and re-erected somewhere else. The repeated modular bays are, perhaps unintentionally well proportioned and the symmetrical composition is essentially classical. The bracing at the tops of the posts are a primitive capital, taking the weight and wind-loads from the roof down into the columns.

The barn is made of materials that could be said to improve with age as they develop a patina and even as they decay. The simplicity of its form and construction are appropriate to its function. It is only clad on its south-east and south-west sides where the wind normally comes from so it looks completely different from one side than the other. The thing I really like is how its appearance and transparency change through the seasons. In late spring and summer the sheep use it for shade and as a sheltered place to spend the night. During the summer it slowly fills up with straw bales and loose metal panels are tied on to the open sides to give more protection from the rain. Over the winter the colour of the bales changes from gold to brown and they are removed a few at a time until it is empty again. The module of the stacked bales is similar but slightly different to that of the structural frame in front so there is an interplay between the two rhythms. The bales form a rough grid pattern that is full of gaps, lumps and frayed ends, imperfections that could be said to have their own order. I would love to make elevations that have as much life and character as these.

The reason I am talking about a humble barn with no architectural pretensions in this way is that it has qualities and evokes feelings that many architect designed buildings fail to do and I am keen to understand why that is. It is not my intention to romanticise the aesthetic of decay. It is much more difficult to design a building for human habitation with all its necessary regulations and the client’s understandable desire for it not to rust and fall apart. Using materials that improve with age and exposure to the elements without requiring too much maintenance makes sense in any building. The idea of an honest structure where the materials are doing what they appear to be doing is seductive but very difficult to achieve in the multi-layered construction required to achieve the level of environmental performance we now demand.

In some ways looking at such buildings for inspiration is not constructive because we are easily distracted by aesthetics and a different set of values from the people who have to use and maintain them. I can be pretty sure this barn was not built with any of the things I have mentioned in mind – it is simply a place to store straw, but it is precisely this conflict that interests me. Development in the countryside is inevitable and farmers need to adapt to different methods and larger scales of agriculture. A structure such as this suggests how that might be done in a way that is obviously man-made but with a degree of refinement and allowing nature a place in the life of the building.