The buildings of the past that we most admire tend to be those made in a way that represents something of the spirit of their age, a sentiment that applies as much to the humble terraced house as to more celebrated structures like gothic cathedrals or Victorian railway stations. We perceive beauty when we sense materials being worked with artistry and judgement by people working to the best of their abilities in ways appropriate to their times. There is something timeless in the way such buildings appeal to the emotions, stepping beyond the constraints of the circumstances of their production to connect with enduring human feelings. So what is an appropriate way of building for our time, and what might it say about our culture to future generations?

In a globalised world where we are bombarded with endless images and limitless potential inspiration, it might seem that we could build whatever we like. With sufficient knowledge, budget and technique it is possible to make something in any historical style, but even if the result is beautifully made, it might feel out of place in our time and might lack a certain energy or spirit that connects it to its own age. You could say that if someone wants to make or own something and appreciates it then it has value and is justified. Perhaps so, but if we don’t develop the thinking of those who have gone before us and make best use of the technology available it suggests a lack of ambition, a failure to ask sufficient questions and to seek new solutions. As architects we need to understand history, make it a fundamental part of our thought, and from it to create something new. Whether it is intended to or not, any building or object says something about the minds of the people who made it, their view of the world and their aspirations. It is an artefact of the culture at the time it was made.

The houses above are in the Somerset town of Street and were built in the 1890s by the Clark’s shoe company who, as Quakers believed in providing good working and living conditions for their workers. As well as housing they built a school, a library and a hall in an Arts and Crafts style and in the 1930s, an outdoor swimming pool. The attention to detail and quality of construction of these buildings expresses the caring spirit in which they were built and their construction is distinctly of its time and place.

A rich variety of buildings is part of a thriving built environment and we can enjoy work resulting from approaches quite different from our own. We all carry a lifetime of experiences, influences, beliefs, prejudices and hopes that determine how we interpret situations and make decisions. Shared economic, technological and cultural conditions inevitably produce trends that are identifiable to a certain time in history but there is ample scope around them for distinctive individual exploration.

Diagram showing insulation and environmental aspects of the Dundon Passivhaus

For me the most pressing challenge we can address as architects is reducing the energy demand of buildings, both in use and in their construction. 42% of the total UK carbon emissions are estimated to come from construction, operation and maintenance of the built environment (UK Green Building Council). The residential sector accounts for 17% of total emissions (2017 UK Greenhouse Gas Emisisons) and 17% of total emissions come from heating and cooling buildings. 6% of total emissions come from carbon embodied in new construction. By reducing the need for heating and cooling and by using materials with low embodied carbon we can make a considerable difference to carbon emissions from the buildings we create.

In our work we are constantly researching how we can improve the environmental performance of our buildings, but always in the context of wider architectural ideas. A defining principle of our practice is that architecture doesn’t have to be sacrificed to achieve excellent energy performance. Achieving a very high standard of energy performance should not on its own be remarkable and hopefully there will soon be a time when all buildings are built to this standard.

I am particularly interested in the question of what potential architectural qualities a very low-energy building might have, and how the building fabric might be manipulated to express the inherent character of its materials and the way they are assembled. In the early days of ‘green’ architecture, buildings wore their solar panels and ventilation cowels proudly as symbols of their environmental ambitions, often concealing a not very well insulated building behind, and seldom with much architectural ambition. If we are serious about conserving energy and reducing carbon emissions we need to eliminate the need for that energy in the first place. Such an approach has certain implications on the building:

- To minimise heat losses the form of the building tends to be compact.

- High levels of insulation require thick walls with deep window reveals.

- High performance windows have quite chunky frames, although these can be partially

concealed by the external wall cladding.

- Overhanging roofs or solar shading to protect the windows from summer over-heating.

These characteristics are a product of the materials available today and a pressing need to reduce our dependency on fossil fuels. As products and technology evolve the resulting buildings will change. For example, the need for thick walls is partly due to our desire to use natural insulation materials that require a greater thickness to achieve the same performance as a petrochemical-based foam insulation. More efficient insulation products may be developed in the future from renewable resources and the need for thick walls might become a blip easily identified as characteristic as of these few decades.

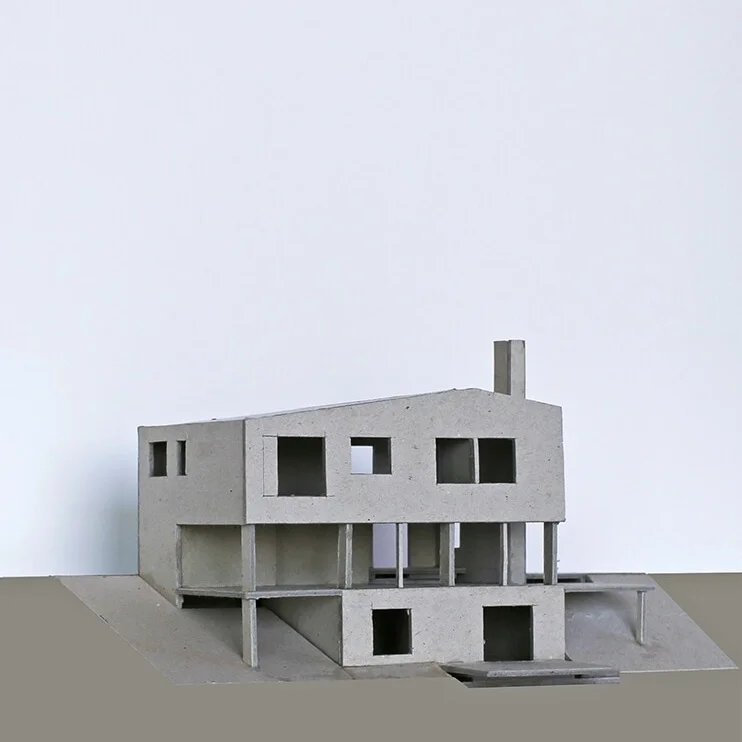

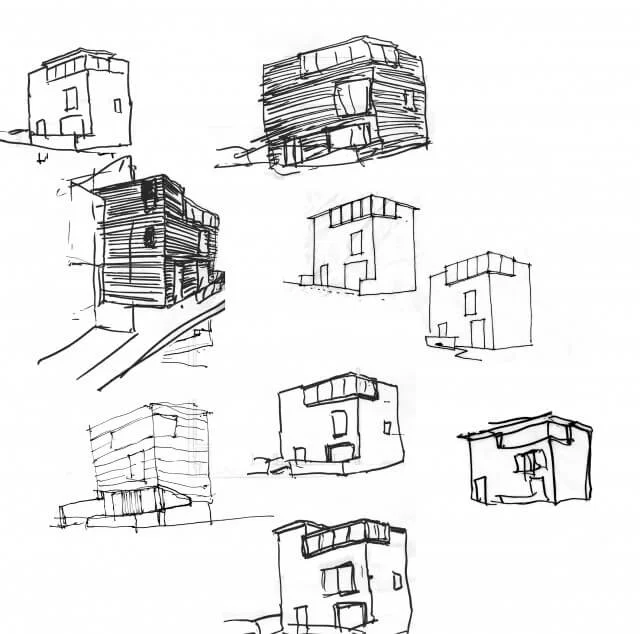

Design models for a Passivhaus in Devon - compact form, large areas of south-facing glazing

Dundon Passivhaus - Thick walls and deep window reveals

Dundon Passivhaus - overhanging roof and veranda provide solar shading to south-facing glazing

The fundamental role of architecture in providing shelter, housing, places for communal activities and for worship has not changed much for thousands of years but the means at our disposal and the ways in which these needs might be fulfilled are constantly evolving. The period since the industrial revolution has seen a huge expansion in technology, engineering and construction techniques. Fundamental to the Modern movement in design (late 19th Century - 1960s) was a belief in technology, that industrial processes and technological progress would result in a better standard of life for most people. We no-longer see technology as a panacea for all our problems and we understand that it often has negative consequences as well as undoubtedly immense benefits. The problems might be unforeseen, or more often there are plenty of people who see them coming but we blunder along regardless. The architecture of the 20th Century has many high points, but there were also serious failings, particularly with poor insulation and damp control, and a lack of regard for the social structures and emotional needs of the communities the buildings were meant to serve.

From the 1960s there was a rejection of the ethos, construction methods and styles of the Modern movement and a reversion to more traditional approaches. The reaction is understandable and there is now a healthy scepticism about any such grandiose claims. In the face of increasing populations, housing shortages and climate change we should be making the best use of technology we can. In that sense the ethos of the Modern movement is timeless and represents a fundamental human endeavour. For most architects this spirit never went away. Zaha Hadid for example described her work as a continuation of the ‘un-finished project’ of Modernism.

Maxxi Art Centre in Rome - Zaha Hadid Architects, 2008

There are many issues or technologies you could chose to address and design is a pluralist endeavour, so there is no single answer. Hadid chose to explore fluid forms, initially through painting and later at the forefront of 3D computer modelling. I visited and wrote about the Phaeno in Wolfsburg and the Maxxi in Rome for Building Design, both of which used self-compacting concrete to create complex curving forms. It is hard not to be impressed by their innovative structural achievements, but beyond spectacle I am sceptical of the benefits of such work, and their detachment from the fabric of the city repeats mistakes that blighted the public realm around some 20th Century buildings. I once asked Hadid what her attitude was to the environmental performance of her buildings and she just smirked awkwardly before her assistant stepped in with some platitudes.

The idea of an appropriate architecture for our time is totally different from a style. Style suggests a look or manner of designing that is affected or superficial, and possibly disconnected from the underlying structure, whereas architecture emerges from the way something is conceived and made. In that sense Modernism is an on-going process. It was only a style that was rejected because it came to represent wider problems with the built environment and social upheaval.

I wrote most of this piece a little while ago and was inspired to finish it having recently read Adam Caruso & Helen Thomas’ excellent book on the architect Rudolf Schwarz that contains a transcript of an address Schwarz gave in 1958 under a similar title, Architecture of Our Times. Elsewhere in the text they quote Schwarz: “The true planner is the person who achieves the one thing that will illuminate his age; he is a faithful tiller of the soil of history. It is incumbent upon him to carefully preserve all fruitful forces, to propagate historical life and to cultivate the future.” I like the wide inclusiveness of the phrase ‘all fruitful forces’, the way it calls for judgement on the part of the designer to gather and examine the possible influences on the project, from the past and present, and to make judgements as to what needs to be included. Architecture is a long-term project. A building spends a fleeting few years in the times in which it was built and then culture moves on. For the rest of its life a building must maintain a relevance to a succession of occupiers and if it is to continue to be appreciated it must appeal to the emotions of future users and be robust enough not to cause them problems. These choices are not just being made for the present, but with the solemn responsibility for the interests of future generations.

Dundon Passivhaus - large areas of south-facing glazing with solar shading