This week Emily & I went for a rare night away at the Talbot Inn in Mells, a 15th Century coaching inn with great food and atmosphere. We had been keen to go there for some time but my enthusiasm was only partly motivated by the victuals. Edwin Lutyens was a frequent visitor to Mells Manor House and designed several exquisite works around the village. In the church are two memorials to members of the Horner and Asquith families killed in the 1st World War. One is an equestrian statue by Sir Alfred Mannings on a plinth by Lutyens, a miniature version of the Whitehall Cenotaph which I can’t get too worked up about.

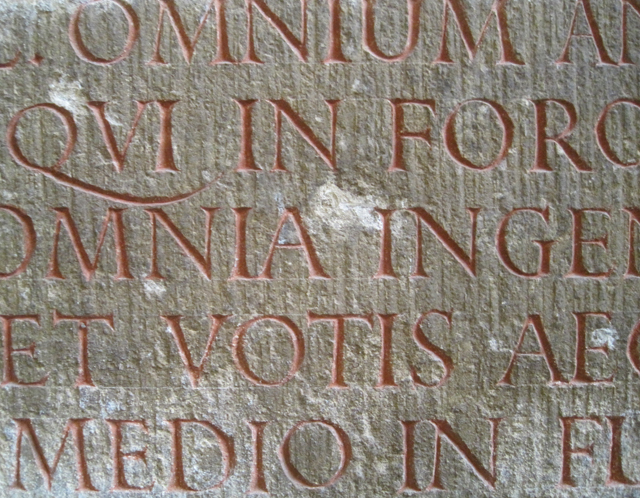

The other, to Raymond Asquith, is a simple bronze wreath mounted above an inscription engraved directly in the Doulting stone of the south wall of the church by a young Eric Gill. Asquith’s sword used to hang on the two hooks beneath the inscription but was removed by the family for safe-keeping. The afternoon sun streams in through the west window above but only hits the memorial indirectly so the light is warm but soft, with gentle shadows. The red pigment is faded and the inscription feels ephemeral as if it will eventually dissolve into the wall surface. It reminded me of the centuries-old graffiti you see on historic sites in Italy recording the fleeting passage of travellers. Engraving the inscription directly in the stone has an immediacy lacking in the usual memorial plaque in a different, ‘finer’ stone like marble or granite. It feels a very personal, heart-felt act, one that links the words and the memory of the person directly with the very stones of the place where he lived.

Outside in the churchyard two lines of clipped yews designed by Lutyens lead off from a north door to the fields beyond. Siegfried Sassoon is buried in the churchyard.

The village war memorial, designed by Lutyens in 1920 has a plinth of Doulting stone that emerges from the slightly coarser retaining wall along the roadside. Two stone seats follow the concave curve of the wall with a central figure of St George on a Doric column. A clipped yew hedge follows the form of the stone walls below. I really like how the yew has been used in a similar volumetric way to the stone, in blocks slightly scaled down from those of the plinth. Recessing the wall like this towards the top of an elevation was a typical Lutyens trope in buildings of the period such as the Midland Bank in Manchester and the Whitehall Cenotaph. Using yew instead of stone for the upper section blends the memorial into the surrounding vegetation, a village version of what started as an urban idea.

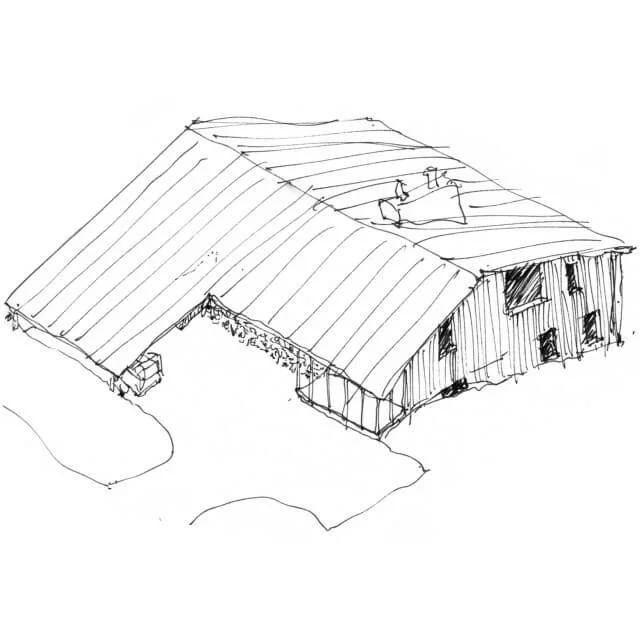

Not far away is this perfect little shelter that once housed one of the village taps. Designed by Lutyens in 1909 the tap is covered by a triangular stone-tiled roof supported on three triangular piers. It is open on two sides and the third consists of a stone wall and seat with an inscription by Eric Gill. Like the war memorial the shelter morphs out of an existing stone wall that anchors it in the fabric of the village. A cascade of stone steps echo the plan form of the shelter and lead down to the riverside. The stone piers taper slightly towards the top where recessed ‘capitols’ support a moulded timber eaves beam. The proportions and detailing are immaculately judged to be simple yet refined and there is nothing patronising or folksy in the way the famous London architect approached a small commission in a distant village.