This genteel town square has all the features of a well-loved English market town - a mixture of shapes and sizes of shops, services and public buildings, each apparently a confident product of its time despite all being built in the late 1990s, getting along with one another just fine. It is all rather pleasant and seems to work very well. So why do most architects react to the merest mention of Poundbury with convulsions of derision and contempt?

On Saturday I spent the day there on a tour organised by the Architecture Foundation, with Owen Hatherley, Isabel Allen and me leading a walk exploring the town. Owen has written about what he sees as the rather sinister authoritarian overtones behind the project and you can read some of his writing here and here. Isabel's experience as design director of house builder HAB brought some really useful insights into the realities of trying to raise the bar for quality in housing development and place making.

As Owen pointed out, your view of Poundbury will depend on whether you see it as a housing estate, of which it is undoubtedly an impressive example, or as a model town, which carries wider political, economic and social connotations.

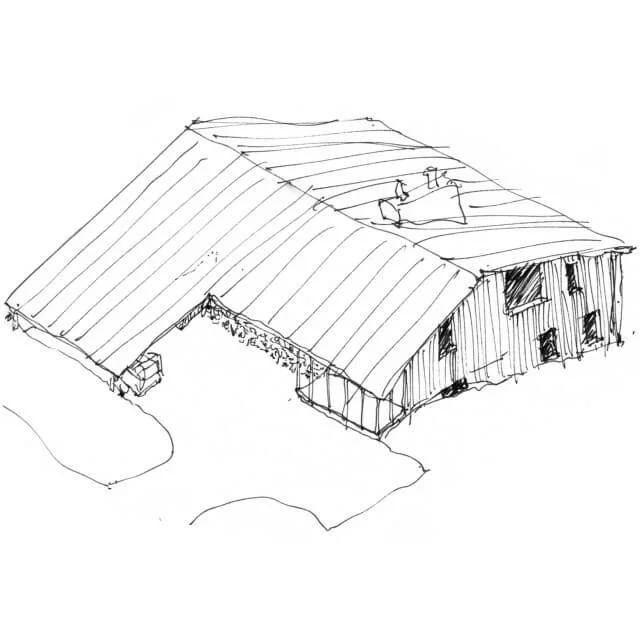

The Poundbury Development Brief proposes the classical style for the central core area and vernacular style for the outer 'village' areas and this is largely been adhered to. It suggests that design cues are taken from buildings within Dorchester and the surrounding area, but the influences evident in the buildings are from much wider sources, and there is certainly something Germanic about the steeply sloping roofs in the first phase of development that is noticeably absent in the later phases.

An obvious repost to a criticism of the traditional style is to ask for an example of a development of similar size and ambition built in a Modern or Contemporary style, and it is hard to think of one. Accordia in Cambridge, or Alvaro Siza's housing at Evora? There are a number of excellent housing schemes with an urban dimension by architects like Peter Barbour, Ash Sakula, Mikhail Riches but they are much smaller. I was keen to get past the issue of style to see whether the place actually works as an urban realm and as a community.

At the centre of Poundbury is Queen Mother Square, a dramatic leap in scale from the surrounding two and three storey housing where any pretense at references to local precedent has been thrown out of the window. The four main buildings are so different in scale and style that it feels like a Disneyland model of itself. The gin palace on the corner, designed by Francis & Quinlan Terry is the best of the bunch, and the only one with an interior that matches the glamour of its exterior. Strathmore House, the St Petersburg palace next to it feels most out of place, and block opposite containing a Waitrose with flats above is large and bland. As the effective market of Poundbury the supermarket could have been given a tall interior, perhaps a vaulted ceiling, but no - it is a typical low, metal paneled Waitrose ceiling. The development of luxury Hyde Park style flats on the north side and their tower actually sit rather well.

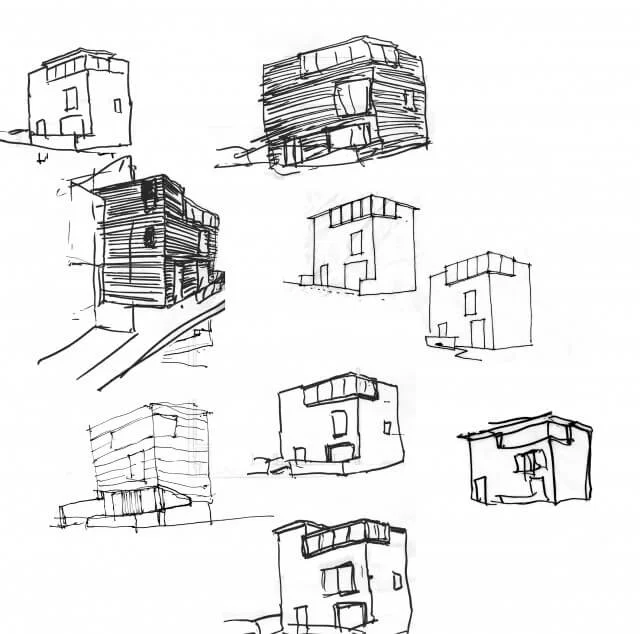

In a traditional town, there is a relationship between the scale and grandeur of a building and its function. The housing tends to be modest, perhaps 2, 3 or 4 storey, and the buildings with a civic or public function are larger with bolder forms or more embellishment. Leon Krier's sketch above shows his vision for how the important public buildings should be interspersed among the more prosaic housing and economic functions.

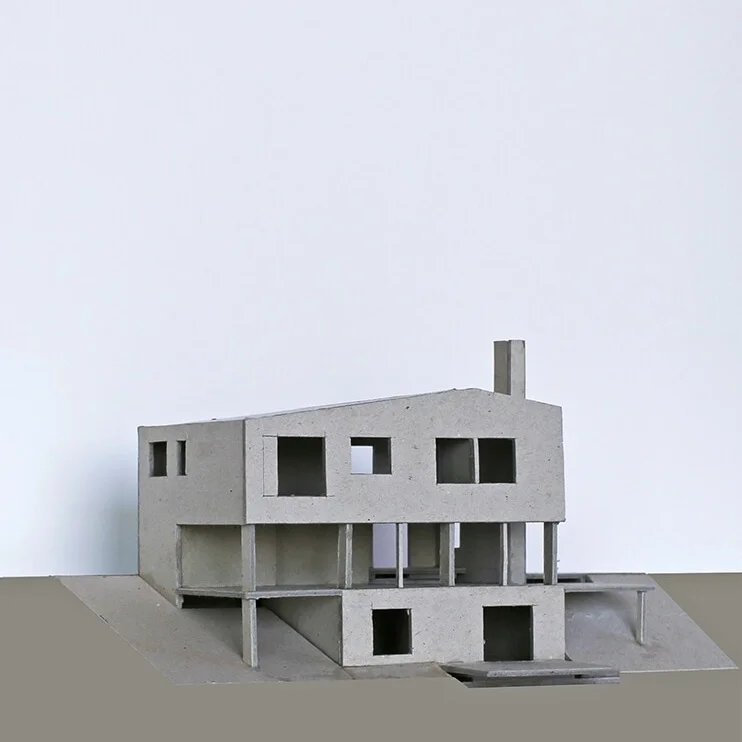

At Poundbury the two grandest buildings contain luxury flats, while more important civic functions make do in more humble quarters. The district looks like Krier's sketch but the functions have got mixed up. Most pitiful is the school (below), arguably the most important building in any community, housed in a bog-standard design & build shed with no architectural or civic ambition.

And what's this? A church, or perhaps an art gallery? No, it's a carpet shop, with a few flats above. The arts centre has to make do in an industrial unit outside the ramparts with other equally subversive activities like Dorwest Herbal Pet Care on the other side of the ring road. And the imposing looking Victorian warehouse at the top of the street below? That's an old people's home. According to Krier, in his book Architecture - Choice or Fate, "If museums look like factories and churches like industrial warehouses, a basic value of the state is in crisis."

In towns and cities we usually welcome the re-use of redundant historic buildings as something that enriches the urban environment and we are used to seeing the likes of Victorian warehouses working very well as flats. The structure of the city is already established so the change of use does not necessarily threaten our understanding of the civic structure and often contributes to the revitalisation of a derelict area. At Poundbury the difficulty is that the civic functions do not already exist and the money is not available to give them buildings of sufficient status, but money is available from buyers of expensive housing, so that is where it is spent.

These examples expose the fundamental paradox of Poundbury. It is designated as an 'urban extension' of Dorchester, not as a town centre, so in the planners' eyes it is a subservient housing estate, and should not be allowed to suck too much life out of the existing town. According to Krier the Duchy were originally promised funding for a District Court, Leisure and Sports Centre but this has now been withdrawn. Prince Charles and his team seem to view it as a model town that could exist independently of Dorchester, with its own centre and hierarchy of sub-centres. They want grand public buildings, but those functions are already in Dorchester, or there is just not sufficient public money, so they have persisted in building a piazza for their town, the only viable function for which is luxury flats.

In The Architecture of the City, Aldo Rossi describes how a monument "summarises all of the questions posed by the city" and that "by virtue of its form its value goes beyond economics and function". The private residential tower and palace have no value in terms of shared civic ideals, apart perhaps from an affirmation of conservative values, but they certainly provide a clear answer to the question of who holds the power in our society, rich private companies and individuals, or public institutions.

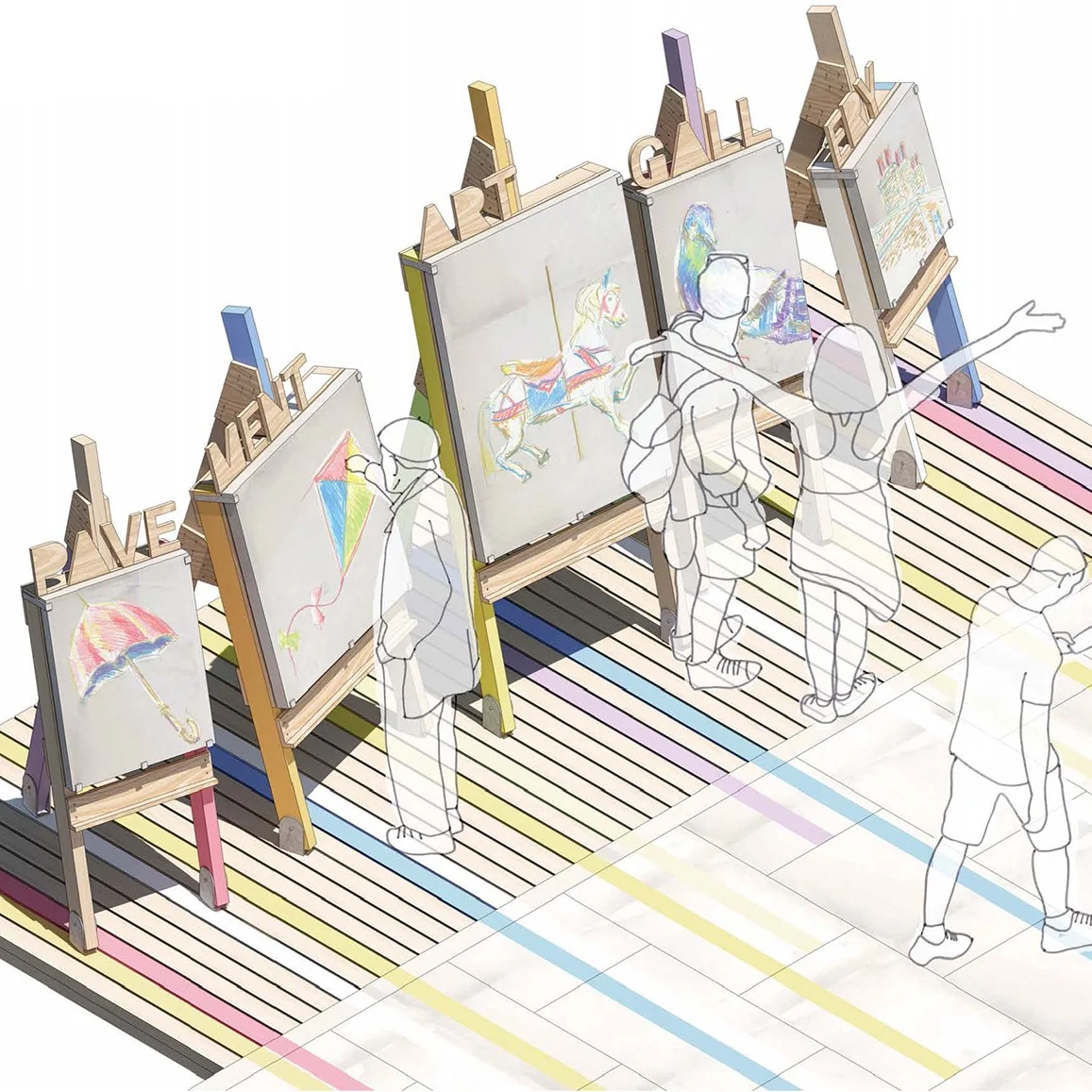

Above are two of Leon Krier's sketch plans. The right hand drawing shows how mixed-uses (in black) define the main thoroughfares and squares. The one on the left shows the four 'urban villages' and the thick black lines around the perimeter emphasise the edges. Defining the edges on all sides is intended to avoid sprawl and encourage a direct relationship between the housing and the surrounding landscape. We used a similar concept in our Europan competition winning proposal for Sky Edge in Sheffield.

Below is a view along the southern edge, where a broken wall of houses and terraces overlooks the ring-road. Below that is a view east across the park towards Dorchester, where the Duchy have built their own edge of MacIntosh/Voysey villas which help define the park as a space and avoid the Poundbury residents having to look at ordinary housing on the other side.

The secondary public spaces are very successful. This elegant crescent of houses by Ben Pentreath could be straight out a London estate like Lloyd Square in Islington, defining a small park with a row of trees that pre-dates the development. The park is one of the only public green spaces and its looseness is a welcome relief from the tightly controlled streetscape. Ben Pentreath has had an increasing role since 2009 overseeing the development of Poundbury and he seems to have improved the detailing and quality of construction, both of which were rather thin on the earlier phases.

Below is the Buttermarket, a sloping square that manages to incorporate raised colonnades that are accessible to wheelchairs through careful manipulation of slopes and levels. The big first floor terraces are great - outdoor rooms that encourage something that is very rare in British culture, the overlapping of private and public realms. Residents can sit or eat out and engage with the life of the public space while still being in their own partially protected zone. The execution is clever too, extending the historic precedent to be useful in the way people want to live today while retaining the feel of the Georgian model. Comfortably Clifton while tipping their hats to New Orleans.

On a Saturday afternoon the streets were eerily deserted, like an episode of Doctor Who just before something weird happens. We were struggling to fathom on the tour how a population of less than 4000 people can sustain so many shops. Some aren't even fronting the main squares and developers struggle to let retail units below flats in many towns, so perhaps they have very low rents in order to ensure the ground floors are active, or perhaps the Duchy are hoping Poundbury becomes a tourist destination like Chipping Camden or Stamford.

This nursing home by James Gorst Architects is one of the better buildings:

Below is some more typical housing, set in a well proportioned street with varied rooflines, different materials, taller buildings at the junctions and owing much to Gordon Cullen's book The Concise Townscape. There are mews between the backs of each row of houses for parking, with 'sentinel' dwellings for security and to break up the banks of garages.

A founding principle of Poundbury is its sustainability and there is an anaerobic digester on a neighbouring farm, part funded by the Duchy that can supply methane gas produced from farm waste to 4000 houses in winter. An electric bus runs between Poundbury and Dorchester, powered by electricity from the digester. On the building fabric side their record is disappointing. Apart from 11 'eco homes' that claim to have U values 30% better than current regulations, none of the buildings appear to be built to anything better than building regulations standard which is a low bar. There is a target of 20% of energy from renewable resources but a more intelligent approach would be to reduce the demand for energy in the first place using a fabric first approach, with very high levels of insulation and air tightness. Given the Prince's knowledge of and interest in environmental issues this seems pretty poor.

Much is made of the architecture, but nowhere in the publicity is there any mention of a landscape architect. In a development with 150 acres of landscape (60% of the total area) it seems odd not to have a stronger strategy and vision. Most of the open space is around the perimeter where the planting is still being done so it still feels a bit bleak. Within the urban realm there are lots of street trees, some of which are over 20 years old now in phase 1. All the houses have shrubs growing in front of them, which looks pretty but they are only serving a decorative function. The gardens are small but there isn't much space for children to play except out on the perimeter. There are allotments, but they are right out on the western edge by the A37 and no fruit trees or even benches. I'm told there is a sustainable drainage scheme so it seems a missed opportunity not to incorporate areas of water and swales into the landscaping.

Among the residential streets I came across this real old house from 1875 which has a big garden full of plants, an old wooden fence and a straggly hedge. Its size seems profligate compared to its neighbours and I definitely support the idea of small gardens in a compact town as long as there is sufficient green space. What was refreshing about it was the un-manicured freedom of it, the wider opportunity for personal expression compared to the regimented streets around.

One of the great achievement of Poundbury is that the benefits of the urban environment are shared by all its residents, 35% of whom are in 'affordable' housing, and profit from the luxury flats presumably helps pay for the quality of the rest. Benevolent dictatorship has its advantages and a strong vision and long-term intensive management are crucial to its success. The Duchy of Cornwall also owned the land so did not have to buy it on the open market. Unfortunately most housing in the UK is built by commercial companies with a very short-term view, and the upkeep of any public facilities is passed on to cash-strapped local councils. The uplift in value of the land that might help fund construction has already gone to the land owner, so developers are unwilling to invest in the design time, materials and future management required for this quality of public realm. This is precisely what makes Poundbury a difficult model for other commercial developments to follow.

Did you spot any people ? I wasn't trying to avoid them, there just weren't many about.