Over the last couple of months I’ve been challenging the most ill-conceived piece of planning legislation that I’ve come across since working as an architect. Permitted Development is a very sensible policy that enables certain development to be carried out without applying for planning permission. It has always been restricted to minor works that would not have a detrimental affect on the appearance of a building or the landscape. It allows people to alter their homes or businesses without undue expense or red tape and it frees up the planning system from dealing with unnecessary applications. An amendment was introduced in April 2013 that allows any building that was in agricultural use to be converted to pretty much any use except residential. The policy could have some pretty grotesque results – I’m picturing battery chicken sheds being converted to hotels, but it could provide some very useful farm diversification income by allowing a barn to be used for offices or warehousing, or a community use such as a meeting room or village hall. There hasn’t been a big take-up of such opportunities though. Government statistics show that in the 9 months from April to December 2014, only 166 Notices were received in England for conversion of agricultural buildings to other uses, of which 22% were rejected.

In April 2014 however, the act was extended to allow conversion of any building in agricultural use to residential use. Allowing residential conversion hugely increases the potential impact of the policy because of the profits that can be made and the demand for housing in rural areas. Instead of planned development in areas of low environmental impact agreed by democratically elected councils, the permitted development rights encourage the peppering of the countryside with houses and an erosion of the rural character of the landscape. Most agricultural buildings are in open countryside, often only with track access that would need to be upgraded, so residential conversion with all its associated domestic paraphernalia would have a much wider impact than the footprint of the building itself. Unless the planners specifically demand it, there is no requirement to submit a design for the resultant dwellings so they would mostly be built in the standard developer vernacular which tends to a suburban rather than a site-specific or rural style. The outlook over numerous patches of agricultural landscape would become less rural and more domesticated.

Government statistics released in December 2014 show that in the first 9 months that the policy has been in force, a total of 1800 Prior Approval Notices have been submitted in England, of which 994 have been refused (55%) and the rest allowed. More applications were refused in the October – December (58%) than in the previous two quarters (52%), suggesting that some local authorities are realising they do have the power to reject them if they want to. The attitude of local authorities varies considerably. For example South Somerset have refused 62% of notices received (18 out of 29), compared with Mid Devon which only rejected 26% (19 out of 74). At the extremes, East Devon rejected all the Notices they received (16 out of 16) whereas Hambleton in North Yorkshire allowed all 17 they received.

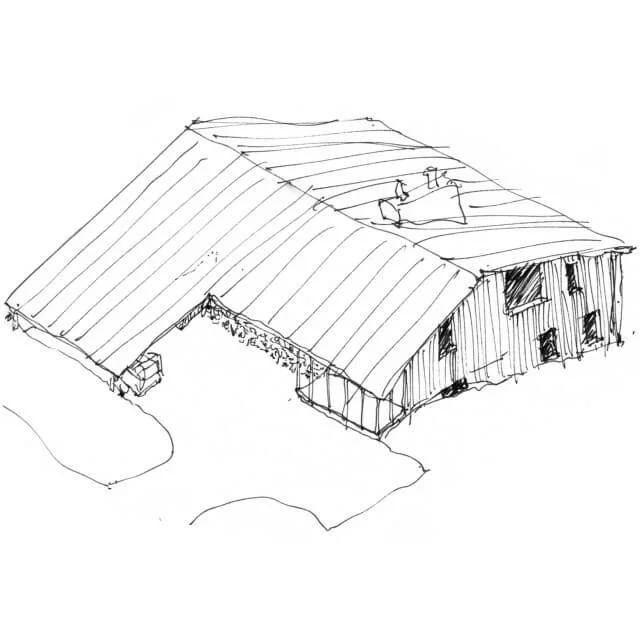

I first became aware of the new policy after I saw someone measuring up the hay barn in front of our house back in September. Aside from being rather fond of the barn (see my previous post from June 2013), it would completely ruin our rural outlook if we looked directly at another house. I won’t deny NIMBYish motives for my pique, but there are principles at stake that would have a hugely detrimental effect on the character of the countryside if many such conversions were allowed to go ahead. To illustrate the scale of the threat, there were two other similar Notices under consideration at the same time in the fields around our village alone so presumably the same is happening around many villages around the country.

A Prior Approval Notice was duly submitted by the owner and when I spoke to South Somerset planners I was told there were very few grounds on which they could reject it. I was dumbfounded that they did not seem minded to put up any resistance so I combed through the legislation and put together a pretty robust letter explaining how the proposal was contrary to planning policy and that they could not let it go through. To our great relief it was rejected in January. The policy is very much open to interpretation and local authorities have been feeling their way somewhat but revised guidance published on March 5th 2015 does provide more clarity. For the interest of anyone wishing to object to such a notice (and yes, you can object) I have summarised my interpretation of the policy and our experience below.

There are a number of criteria the agricultural building must conform with to come under class Q of the Permitted Development Order and be eligible for conversion:

– The site must have been used solely for agricultural use on March 20th 2013.

– The total number of dwelling units on the agricultural unit must not exceed 3, so if there are already a farmhouse and a couple of mobile homes for agricultural workers then another dwelling would not be permitted.

– No work may have been carried out under Permitted Development since March 20th 2013.

– The proposed dwellings must not extend beyond the existing footprint.

– The building cannot be listed, in an AONB, National Park, SSSI, conservation area etc.

– Demolition must be ‘partial’ which implies at least some of the existing structure must be retained, although there is no definition of a minimum amount.

– The building works required to convert it to a dwelling can only consist of installation or replacement of windows, doors, roofs, exterior walls, drainage and services.

These last 2 points are important. The last point does not mention foundations or floors which implies the new dwelling must re-use the existing foundations, ground floor slab and only be single storey. The barn in front of us is a simple steel frame structure with no ground slab. The steel structure is not strong enough to support a house and not substantial enough to be ‘converted’ to a dwelling. This view was taken by the inspector in dismissing an appeal against refusal of a prior approval notice for a similar barn in Doddiscombsleigh, Devon on 21 October 2014 (ref: APP/P1133/A/14/2223350). The March revised guidance states that “It is not the intention of the permitted development right to include the construction of new structural elements for the building. Therefore it is only where the existing building is structurally strong enough to take the loading which comes with the external works to provide for residential use that the building would be considered to have the permitted development right.”

If a building qualifies under these criteria there are very few factors the local authority can take into account under which the Notice might be rejected. They are:

– Transport of Highways impacts

– Noise impact

– Contamination risk

– Flood risk.

– Whether location or siting makes conversion impractical or undesirable.

The last point is crucial and would appear to allow the council to reject the application for a wide range of reasons. As to whether it is desirable, Paragraph N (8) (b) of Part 3 states that the council must have “regard to the NPPF (National Planning Policy Framework)… as if the application were a planning application.” The question is whether the residential use of the structure is justified and desirable in the light of national planning policy which seeks to restrict new housing development in the countryside.

The March 2015 guidance states that “the local planning authority must only consider the National Planning Policy Framework to the extent that it is relevant to the matter on which prior approval is sought, for example, transport, highways, noise etc.” but this is a circular argument because one of their factors is whether location or siting makes conversion impractical or undesirable. The guidance states that because “an agricultural building is in a location where the local planning authority would not normally grant planning permission for a new dwelling is not a sufficient reason for refusing prior approval”, although it does go on to give reasonable examples of why approval might be refused.

Several appeal decisions have now been made that confirm the priority of NPPF policies over permitted development policy. In his report rejecting an appeal against refusal of a prior approval notice for a barn conversion in Ripon, Yorkshire on 18 August 2014 (ref: APP/E2734/A/14/2220495), the inspector stated that the proposed development “would fail to enhance the immediate setting and cause significant harm to the character and appearance of the surrounding area”.

In response to a Notice the Local Authority can insist on prior approval design and external appearance of the dwellings. These are the elevations that were submitted for the barn in front of us:

Nice.

While I understand the need to think laterally to find ways of providing housing in rural areas I can’t help concluding this policy is detrimental to the character of the countryside and appallingly short-sighted. Any sensible housing policy should take local needs into account and under permitted development the local community gets no say in what sort of dwellings might be provided. The resulting houses have inevitably been aimed at the higher end of the market, particularly incomers because of their size and location which does nothing to address affordable housing needs. It is simply another example of the countryside being eroded with inappropriate development.

The evening we found out the barn in front of us might be converted to a house, I looked out to see a barn owl circle around and land on the barn. I haven’t seen one near it before or since.

Update: 20 January 2016

The applicant appealed against the refusal for the barn above and the appeal was dismissed (ref: APP/R3325/W/15/3129012). South Somerset gave two reasons for having rejected the prior approval notice:

1. "that the location and siting would be impractical and undesirable by reason of the introduction of a residential use, exacerbated by a poorly detailed design that would be harmful to the character and appearance of the countryside."

2. "that there is a lack of convincing evidence that the conversion would not require new structural elements such as foundations."

The inspector concluded that "it has not been demonstrated that the building could be successfully converted without significant new building operations outside the definition at Q.1(i). Therefore the scheme would not qualify as permitted development." He did not comment on the first reason.

Update: 13 February 2017

In November 2016 a High Court ruling provided a bit of much-needed clarity on the subject of what level of work constitutes conversion of an agricultural building under Class Q. The applicant's Permitted Development notification to Rushcliffe Borough Council in Nottinghamshire for 'conversion' of a steel framed barn 30 x 8m was rejected and a subsequent appeal was dismissed.

The inspector considered that the agricultural building would not be capable of functioning as a dwelling without substantial building works, including the construction of all four exterior walls. She considered that for the development to amount to a "conversion" the nature and extent of the works needed to fall short of a rebuild. The proposed works to the agricultural building went "…well beyond what could reasonably be described as conversion…".

The applicant appealed to the High Court (Hibbitt v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government [2016] EWHC 2853) and the High Court ruled against the applicant and upheld the inspector's decision.

The ruling focused on whether the works would be a conversion or a rebuild. The Court ruled that, "The development was in all practical terms starting afresh, with only a modest amount of help from the original agricultural building." and that "There will be numerous instances where the starting point (the "agricultural building") might be so skeletal and minimalist that the works needed to alter the use to a dwelling would be of such magnitude that in practical reality what is being undertaken is a rebuild."

Paragraph 105 of the NPPG states in relation to Class Q that it is not the "… intention of the permitted development right to include the construction of new structural elements for a building".

Paragraph 55 of the NPPG states that local authorities should avoid new isolated homes in the countryside unless there are special circumstances. The judge agreed that "permitted development should be construed conservatively and narrowly so as to ensure that it struck an appropriate balance between the advantages of automatic approval and the more onerous process of substantive appraisal and did not do damage to wider policies." Furthermore, Class Q permitted development legislation was "intended to be suitable for fast track, clear cut, developments; not short cuts for complex cases which might raise significant issues under Paragraph 55."

The ruling still leaves some grey areas, particularly in the assessment of whether the extent of the works precludes them from coming within the remit of Permitted development. In this case, the judge agreed with the inspector that "the works went a very long way beyond what might sensibly or reasonably be described as a conversion."

The judge's ruling is clearly written, but for some interpretations of the case, see the links below:

Hewitsons

Practical Law

No. 5 Barristers Chambers