In both Britain and Germany the spirit of the period following the Second World War was to sweep away the remains of partially destroyed buildings in search of a future that embraced technology and the future. Certain important historic structures were re-built as close as funds would allow to how they were before, but there aren’t many good examples of buildings that bridge the gap between old and new, where surviving old fragments were integrated with new elements into a successful new whole. At Coventry Cathedral for example, the new cathedral is placed adjacent to the ruins in a picturesque manner and they do not touch.

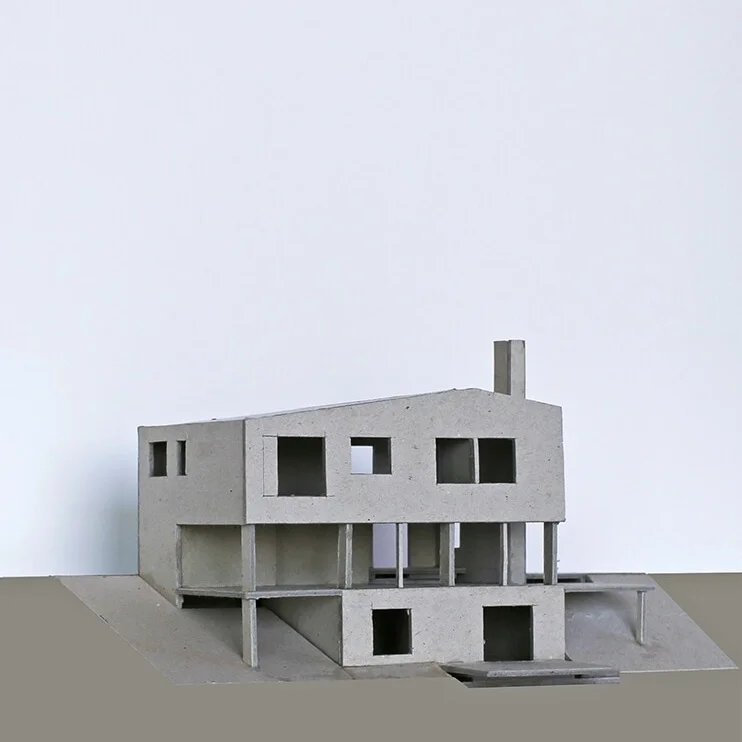

I first saw the work of the Bavarian architect Hans Döllgast on a visit to Munich almost 20 years ago and I was profoundly affected by his approach of ‘creative reconstruction’. His best known work is the reconstruction of the Alte Pinakothek (completed in 1957), the gallery for Old Master paintings originally completed in 1836 to the designs of Leo von Klenze in a neo-Renaissance style. The gallery was badly damaged in the Second World War and many people called for the ruins to be pulled down and replaced with a new building. Döllgast took a more nuanced approach that attempted to make the history of the building visible, filling in the gaps in the ruins with a stripped down form of construction that maintained the proportions of the original, but using bricks from the rubble of destroyed buildings and without the classical detailing. Most dramatically, the new construction emerges directly out of the old, with no glazed links or shadow gaps to separate them. The historic fabric, wartime scars and frugal 1950s work are bound together into a new construction that feels whole, inclusive of all the elements of its history.

Döllgast moved the entrance and created a vast central hall dominated by a pair of symmetrical staircases that lead from the entrance hall to the galleries above. The ceiling is painted concrete and the brick walls are finished with what looks like a slurry that blurs the distinction between brick and mortar and makes the wall feel more homogeneous. I fell in love with its brickwork when I saw this building for the first time and the bare painted internal brick walls of our Newington Green House were a direct response to my experience of it.

Döllgast's approach has been highly influential on two recent reconstruction projects, the Neues Museum in Berlin by David Chipperfield Architects and Julian Harrap, and Astley Castle in Warwickshire by Witherford Watson Mann Architects.

Döllgast was involved with several other reconstruction projects around Munich, including work to three of the city's cemeteries. I went to the Alte Südfriedhof (1955) where most of the buildings and enclosing walls were destroyed in wartime bombing. Missing sections of the walls were reconstructed in simple brickwork and a steel and timber cloister was built on one side to Döllgast's design. Several small structures were built from bricks salvaged from the rubble. The new elements are positioned where destroyed buildings were located and their proportions are similar. The steel cloister feels almost temporary and without style, yet its proportions and rhythm give it immense dignity and pathos.

The Basilica of the Benedictine Abbey of Sankt Bonifaz was gutted and half its length destroyed in the Second World War. Between 1946 and 1950 the remaining half was reconstructed to the designs of Hans Döllgast. The interior is austere, with white painted brick walls and a timber trussed roof. The only visible remnants of the original building inside are the columns which have a powerful presence, mainly free-standing but sometimes subsumed in the newer brickwork. Since the original reconstruction the interior has been significantly altered to jolly it up and from the description on the Abbey's website I get the impression the management isn't enamoured with Döllgast's work. At the bottom is a sketch and photo of how it was in 1950.

Outside in the entrance loggia there are some gorgeous details where a little stair climbs to a door in a rough brick wall inserted in one end of the porch. The metalwork is particularly fine.

I find the separation of old and new elements that occurs in many extension or reconstruction projects fussy and I think the way different layers of history are bound together in Döllgast's work is much more representative of the way our own lives play out, as palimpsests, not in neat compartments.

The Basilica as it was in the early 20th Century above, and as it is today below.

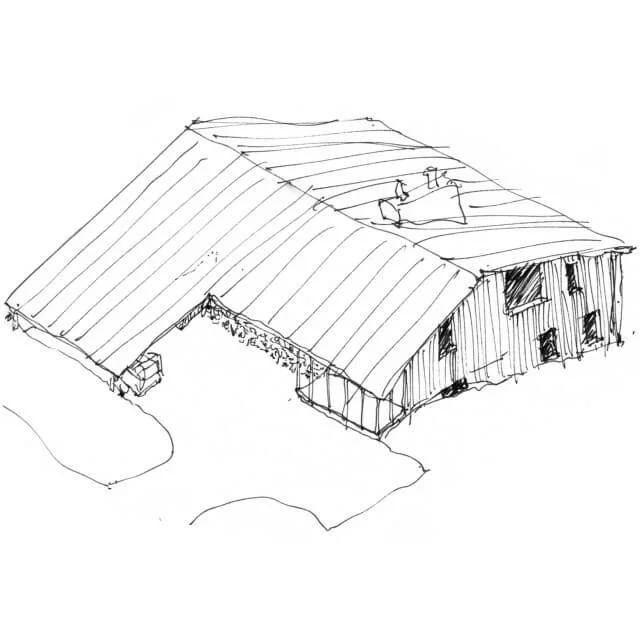

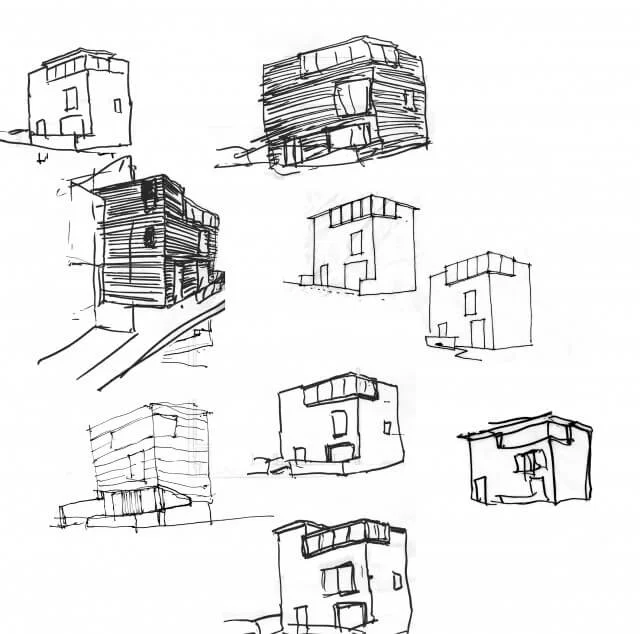

Döllgast's sketch of the proposed reconstruction (left) and a photo from 1950 of the church as originally reconstructed (right).